By Manuela Macchi written for and published by LawInSport.com on the 1 April 2015. View the original article here.

Trade marks in sport are commonly constituted of word or logo marks like ‘MANCHESTER UNITED’ or Nike’s famous ‘swoosh’ logo .

Registered protection of trade marks is the safest and most cost efficient way of obtaining an easily enforceable trade mark right. Whilst some jurisdictions like the UK afford protection to non-registered trade marks that have acquired goodwill through their use, the enforcement of these non-registered rights relies on the expensive and time consuming exercise of evidence gathering in relation to the use of the mark, whereas a trade mark registration certificate is prima facie evidence of the existence of the associated right.

In recent years, the sports industry has seen a growing number of registrations and attempted registrations of marks that differ from what is considered the more traditional words and logos (as above), which can be broadly categorised as “non-traditional” or “unusual” trademarks. This article takes a trip through examples of such non-traditional trademarks, and explores the protection that sports brands can achieve from their registration, a process that, in the author’s opinion, remains underutilised despite the potential that registration offers to an industry that increasingly relies on the exploitation of Intellectual Property (IP) and IP related rights.

WHAT ARE NON-TRADITIONAL TRADE MARKS?

While there is no specific definition, non-traditional trade marks are generally considered to consist of:

- olfactory (used in smelling or relating to sense of smell);

- taste; and

- sound/musical and 3D marks.

There are also a number of other types of marks (as we shall see below) that can also be considered unusual (and in fact from the author’s experience unusual marks crop up in sports more frequently than in other industries).

REGISTERED PROTECTION FOR NON-TRADITIONAL TRADE MARKS

Obtaining trade mark registration for non-traditional and unusual trade marks generally faces two challenges:

- the requirement for graphic representation; and

- the hurdle of examination of the mark’s distinctiveness.

For 3D marks, there are also limits pertaining to their nature and functionality.

THE REQUIREMENT FOR GRAPHIC REPRESENTATION

Article 2 of the EU Directive 2008/95/EC (Article 4 Community Trade Mark Regulation 2009 (“CTMR”)1) defines a trade marks as follows:

“A trade mark may consist of any signs capable of being represented graphically, particularly words, including personal names, designs, letters, numerals, the shape of goods or of their packaging, provided that such signs are capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.” 2

The list in Article 2 of the EU Directive is non-exhaustive and the Office for the Harmonisation of the Internal Market’s (OHIM) Examination Guidelines3 explain at Part B, Examination Section 4 – 2.1.1 that the requirement for graphic representation is dictated by the need to define the mark and the subject matter of protection, leaving out elements of subjectivity in identifying and perceiving the mark. For this reason – the Guidelines go on to say – graphic representation must be unequivocal and objective.

The European Court of Justice‘s (‘ECJ’) (now the Court of Justice of the European Union) watershed decision on the requirement for graphic representation was issued in the Siekmann case4 – later confirmed and developed in the Libertel case.5 The Siekmann decision defined what “graphic representation” means in the terms of Article 2 of The EU Directive:6

“[It] must enable a sign to be represented visually, particularly by means of images, lines or characters, and that the representation is clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective.”

OLFACTORY MARKS

Pursuant to the Siekmann decision, the applicant’s community trade mark (CTM) application for an olfactory mark identified with the description “smell of ripe strawberries” was finally refused registration.7 The impact of this decision was immediate in relation to olfactory marks.

Prior to the Siekmann decision, two interesting examples of sport related olfactory trade marks had been granted protection. First, “The smell of fresh cut grass” had been accepted for CTM registration8 in respect of “tennis balls”; OHIM had evidently regarded the description “the smell of fresh cut grass” as sufficient to define the trade mark and subject matter of protection. Secondly, In the UK, there is a trade mark registration for “the strong smell of beer“9 for “darts”. The UK Trade Mark Office, in line with OHIM at the time, considered this description sufficient.

After the Siekmann decision, no new olfactory marks have been registered as a CTM or UK trade mark registration (of the above marks the first has been allowed to expire by its owner, whereas the second is still registered and in force). OHIM’s Examination Guidelines notably highlight in this respect that:

- A chemical formula is not recognisable as a smell by the public;

- A sample is not a graphic representation and is not durable;

- A description does not meet the Siekmann criteria; and

- There is no Internationally recognised classification of smells (unlike the Pantone code system for colours).

Therefore, the outlook at present is that olfactory marks continue to remain incapable of registration in the EU.

TASTE MARKS

The situation for taste marks is identical to olfactory marks for taste marks, with an example of CTM registration10 being refused for the mark identified with the description “the taste of artificial strawberry flavour” in relation to “pharmaceuticals”.

The author is not aware of any examples of taste marks in the sports field and – apart from perhaps the related field of energy drinks, nutritional supplements, energy bars and the like – it is difficult to think of any goods for which a taste trade mark registration might be desirable in the sports industry.

Should the situation regarding the requirement for graphic representation change (see last heading in this article), the author believes that taste trade marks could be of great benefit to the energy food and beverage industry (think, for example, of the distinctive and highly recognisable taste of Red Bull and of this company’s profile and engagement in the sports industry).

SOUND MARKS

Things are significantly easier for registering sound marks. The ECJ’s decision in the Shield Mark case 11 held that a traditional musical notation is suitable to meet the requirement for graphic representation for musical marks; and a subsequent decision by OHIM’s President 12 ruled that a graphic representation consisting of an oscillogram or a sonogram together with a corresponding sound file submitted via e-filing would be acceptable for sound marks that are not musical.

Notably, MGM registered the famous roar of a lion for their entertainment and other related goods and services. The author is not aware of sound marks registered in the sports field in the EU, but a field that overlaps with sports is that of motor industry and Audi has registered jingles used in their adverts as CTM registrations.13

Sound marks, however, are less common in sports than in the entertainment industry where sounds by their own nature lend themselves more easily to being associated with services or products offered. This said, I am still surprised that some car and motorbikes manufacturers have not applied to register the roar of their engines as a trade mark. It should not be difficult to find ‘petrol heads’ who would be easily recognise the distinctive noise of an Alfa Romeo, a Moto Guzzi or a Harley Davidson engine.

MOVEMENT MARKS

Movement marks are marks in motion that distinguish their owner not by a static representation of a gesture (e.g. a photograph), but by a flow of images in movement representing the whole cycle of the gesture (e.g. a video or a sequence of images).

Graphic representation is not a particularly challenging obstacle for movement marks. despite this though, relatively few trade mark registrations for movement marks have been obtained for movement marks in sports. By For example, Mo Fahra’s “Mo-bot” is not registered, but can, in the author’s view certainly be considered part of the athlete’s image rights in a broad sense. This author finds it surprising that more sports gestures are not the subject of trade mark registration and this option may be overlooked by sports brands, or perhaps the possibility of registering movement marks is still little known.

Marks “in motion” seemed to be more difficult to register in the early years of the CTM system, probably due to unclear examination guidelines. For example, although not sport related, the images representing the distinctive way in which the doors of a Lamborghini car open were refused registration14 as a trade mark by OHIM when the application was filed in 1999 even when the images were accompanied by a description, in this case: “The trademark refers to the typical and characteristic arrangement of the doors of a vehicle. For opening the doors are turned “upwardly”, namely around a swivelling axis which is essentially arranged horizontal and transverse to the driving direction.”

However, more recently examples of CTM or UK trade mark registrations for static representations of sporting gestures can be found:

- Gareth Bale’s “Eleven of Hearts” (UK registration) attracted a lot of media attention when the trade mark application was filed in March 2013, but its post-registration surrender in November of the same year went largely unnoticed and seems incongruous with the UK and CTM registrations for the words “ELEVEN OF HEARTS”, which to date remain registered. The reasons for this surrender are unknown, although the subject of some speculation in the trade mark world.15

- Usain Bolt owns various trade CTM,16 registration for two different versions of his “lightning” pose in clothing, sports equipment and other merchandising classes as well as class 41 (and as well as having registered his name and autograph). Broadly speaking, class 41 covers sporting activities.

- Jonny Wilkinson’s stance is registered as a CTM17 in the representation of a silhouette image of the stance in the typical merchandising classes 16 (e.g. printed matter and publications), 25 (clothing, footwear, headgear) and 28 (e.g. sports equipment).

- Older UK trade mark registrations feature Celtic FC’s pre-match “huddle”18 (in classes 6, 9, 14, 16, 18, 21, 24, 25, 27, 28, 30, 41)19

It must be noted that these trade mark registrations would not prevent other people from replicating the gesture on or off the pitch, but only the commercial exploitation of the same or a similar image for identical or similar goods or services as those for which these marks are registered (with some broader scope of protection reaching as far as dissimilar goods and services for goods/services for registered trade marks with a reputation).

This said, in 2010 OHIM’s Second Board of Appeal20 (Decision 23/09/2010 – R 443/2010-2 “Red Liquid Flowing in Sequence of Stills”) overturned a decision refusing registration of Sony Mobile Communications’ movement mark identified by submitting a sequence of images of a flowing red liquid together with a description of the movement represented.

OHIM had originally held that graphic representation and textual description must coincide with what can be seen for it to meet the Siekmann criteria. However, the Second Board of Appeal ruled that:

“‘when evaluating whether Article 4 and 7(1)(a) CTMR21 have been complied with the test to be applied is whether a reasonably observant person with normal levels of perception and intelligence would, upon consulting the CTM register, be able to understand precisely what the mark consists of, without expending a huge amount of intellectual energy and imagination.”

Sony’s mark was accepted for registration as a result.

This could be an interesting development for sports trade marks and as a possible alternative to relying on passing off for certain aspects of image rights such as sports gestures, but this opportunity has not yet been fully capitalised upon by sports personalities or sports brands.

Steering clear of classifying yoga as a sport, we note that in the field of wellbeing activities a UK registration was granted for a 3D yoga app (UK Reg. No. 2607608) which the mark was identified by submitting a sequence of 60 3D images and a description of the movement consisting of a flow of yoga poses. Whilst the images are visible on the UK IPO database,22 requesting a file inspection, likely because of its length, can only access the description. The author believes that the trade mark is intended to be used as a moving image visible to users of the app.

DISTINCTIVENESS AND OTHER ABSOLUTE GROUNDS

Protection of non-traditional marks can also face more traditional objections such as the so-called “absolute grounds” objections23 which are, most notably, objections relating to the lack of distinctive character of the mark, i.e. a descriptiveness of the goods/services that designates or relates to features that confer the mark its value.

COLOUR MARKS

Colour marks are the most common example of non-traditional marks that risk falling foul of the distinctiveness requirements for registration.

Such marks are capable of meeting the requirement for graphic representation (both as single colour and as multiple colour marks), as OHIM and all EU Trade Mark Registries accept identification of the mark by using the Pantone International classification system.24 However, formless or shapeless combinations of two or more colours must comply with the criteria set out in the ECJ decision in the YELLOW/BLUE/RED25 and in the “Colours Blue and Yellow”26 cases. According to these decisions, two or more colours in any conceivable form do not meet the requirement of precision and uniformity established in the Siekmann case and colours must be arranged systematically by associating them in a predetermined form or way.

Interestingly, the colours of Barcelona FC’s jersey are registered as a CTM.27 No reference to Pantone codes is made in the registration, but a description of the colours as “blue and scarlet” and a representation of the colours have been filed:

We note that the registration was obtained by submitting evidence that the mark had been used to a sufficient extent to have acquired distinctiveness. This is an indication that the CTM application must have initially come up against non-distinctiveness objection. Indeed, when a mark is per se non-distinctive, it may still be capable of registration if its owner can produce evidence to the effect that by virtue of its extensive use, the mark has become recognised by the relevant public as its own mark (i.e. the mark has acquired distinctiveness).

3D AND OTHER NON-TRADITIONAL MARKS

Other interesting examples of unusual marks found in sports are include registrations for trophies such as the 3D and silhouette images of the Ryder Cup registered both at UK and CTM level:28

A descriptiveness objection, i.e. an objection to registration based on the fact that a trade mark describes the goods and services for which registration is sought or their characteristics, may have been expected in relation to some goods or services, but the trade mark was registered in both cases without submitting evidence of acquired distinctiveness.

In the absence of specific legislation protecting image rights (with the well-known and little utilised exception of Guernsey), sportsmen try to protect expressions of their individuality via trade mark registrations.

Michael Schumacher was the first sports star to register his signature as a CTM29 and, whilst still technically a simple word mark, Paul Gascoigne was the first to register his nick name, GAZZA, as a UK trade mark in 1990 (now expired)[30] and more recently re-registered it as a CTM[31] (still live). These registrations are attempts to capture and protect expressions of the sports stars’ personality, in the absence of specific protection for image rights as such.

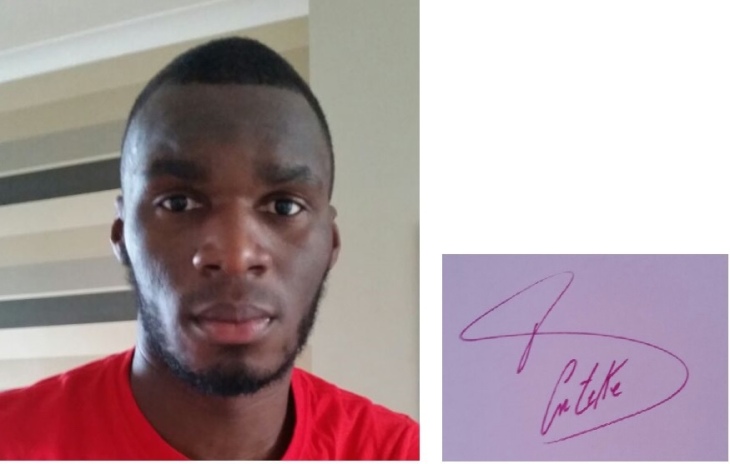

The Belgian football player, Benteke has recently applied for the registration as a CTM of a photograph of himself in combination with his autograph:32

Again, this seems to the author to be an expression of the need to protect image rights in a system that has not yet properly legislated on the subject. Whilst the effectiveness of registering a photograph of oneself to protect one’s image might be questionable, submissions arguing for similarity and likelihood of confusion against infringing trade marks promise to make an entertaining read. The trade mark application, filed in February 2015, is still under examination at the date of publishing.

An often-neglected option for obtaining the protection afforded by registration is design registration. This has been obtained, for example, as a Community Registered Design (‘CRD’) by the Ryder Cup for the tartan created for the occasion of the 2014 matches33 at Gleneagles. This could be a worthy alternative for some multi-colour marks that might not pass the distinctiveness examination for trade mark registration, but meet the novelty and individual character requirements for valid design registration.34 One of the advantages of a registered design application is the ability, by paying an additional fee, to defer publication of the design for up to 30 months from the application date, hence securing a filing date whilst keeping the design undisclosed. The main disadvantage to bear in mind is the Community (EU) Registered Designs can only be renewed for up to 25 years, unlike trade marks, that can be renewed indefinitely.

PROPOSALS TO AMEND THE EU DIRECTIVE

In March 2013, a proposal was presented35 to remove the requirement for graphic representation from Article 2 EU Directive 2008/95/EC (Art. 4 CTMR 2009). Under the proposed amended provision, the relevant part of Art.2 would be amended to read:

- A trade mark may consist of any signs

capable of being represented graphically, in particular, words, including personal names, designs, letters, numerals, colours as such, the shape of goods or of their packaging, or sounds, providedthat such signs are capable of: - (a) distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings.;

- (b) being represented in a manner which enables the competent authorities and the public to determine the precise subject of the protection afforded to its proprietor.

The new provision would afford more flexibility to embrace new technology and a new generation of marks, whilst still achieving a sufficient degree of legal certainty, despite being more open to interpretation. This would be, in the author’s view, an overdue and welcome development. For example, the option to submit a video file for the registration of movement marks could be of great benefit to enhance the protection of athletes’ image rights, and a way of defining taste and enabling registration for taste marks could be exploited by the energy food and drinks industry, as discussed above. These registration would not allow for example Mo Farah to have a monopoly of using the Mo-bot on the track and a registration of Tom Daley’s new dive, which might become his “trade mark move”, will not prevent others from repeat it in competition, but trade mark registration will give the athlete the exclusive right to use that mark in the course of trade for identifying goods and services originating from him. This could be a very powerful tool in advertising.

However, the proposal has not yet made significant progress. On 25 February 2014, the European Parliament adopted (with a large majority) a resolution in favour of the amendment, but the proposal is still being debated and, at a further vote before the European Commission in May 2014, did not secure a majority. Hopefully, 2015 will bring some ground-breaking developments for non-traditional trade marks from Brussels.

—————————————————————————————————————————————-

Copyright Notice

This work was written for and first published on LawInSport.com (unless otherwise stated) and the copyright is owned by LawInSport Ltd. Permission to make digital or hard copies of this work (or part, or abstracts, of it) for personal use, professional training and/orclassroom uses is granted free of charge provided that such copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage, and provided that all copies bear this notice and full citation on the first page (which should include the URL, company name (LawInSport), article title, author name, date of the publication and date of use) of any copies made. Copyright for components of this work owned by parties other than LawInSport must be honoured.

References

- COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 207/2009, The Council of the European Union, February 26, 2009, last viewed on March 13, 2015,https://oami.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/ctm_legal_basis/ctmr_en.pdf

- DIRECTIVE 2008/95/EC, EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL, October 22, 2008, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/ctm_legal_basis/ctm_directive_en.pdf

- ‘Guidelines for Examination In The Office For Harmonization In The Internal Market (Trade Marks And Designs) on Community Trade Marks’, OHIM, October 10, 2005, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/decisions_president/ex14-4_en.pdf

- Ralf Sieckmann 12/02/2002 C-273/00, December 12, 2002, last viewed on March 13, 2015, http://curia.europa.eu/juris/showPdf.jsf?text=&docid=47585&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=189801

- Libertei Groep BV and Benelux-Merkenbureau 06/05/2003 C-104/01, May 6, 2003, last viewed on March 13, 2015, http://curia.europa.eu/juris/showPdf.jsf?text=&docid=48237&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=189879

- DIRECTIVE 2008/95/EC, THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL, October 22, 2008, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/tunnel-web/secure/webdav/guest/document_library/contentPdfs/law_and_practice/ctm_legal_basis/ctm_directive_en.pdf ; Note that the Sieckmann case was actually decided in relation to Article 2 of the First Council Directive 89/104/EEC which was repealed by the 2008/95/EC Directive

- Eden SARL v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market (Trade Marks and Designs) (OHIM), Case T-305/04, October 27, 2005, last viewed on March 13, 2015, http://curia.europa.eu/juris/showPdf.jsf;jsessionid=9ea7d0f130de9956a60b21e240d4ac1a91fc4bfdb637.e34KaxiLc3eQc40LaxqMbN4NchyKe0?docid=65903&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=req&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=236592

- The Smell of Fresh Cut Grass, 000428870, OHIM, December 11, 1996, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/000428870

- Case details for trade mark UK00002000234, UK IPO, October 31, 1994, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://www.ipo.gov.uk/tmcase/Results/1/UK00002000234?legacySearch=False

- THE TASTE OF ARTIFICIAL STRAWBERRY FLAVOUR, 001452853 , January 7, 2000, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/001452853

- Shield Mark, 27/11/2003 C-283/01, Judgment of the Court (Sixth Chamber), November 27, 2003, last viewed on March 13, 2015, http://curia.europa.eu/juris/showPdf.jsf?text=&docid=48435&pageIndex=0&doclang=EN&mode=lst&dir=&occ=first&part=1&cid=192984

- DECISION No EX-05-3 OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE OFFICE, EX-0503 10/10/2005, OHIM, October 10, 2005, last viewed on March 13, 2015, http://oami.europa.eu/en/office/aspects/pdf/ex05-3.pdf

- (Trade mark without text), 009122342, OHIM, May 21, 2010, last viewed on March 13, 2015,https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/009122342

- (Trade mark without text), 001400092, OHIM, November 26, 1999, last viewed on March 13, 2015,https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/001400092

- Case details for trade mark UK00002657917, UK IPO, March 26, 2013, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://www.ipo.gov.uk/tmcase/Results/1/UK00002657917

- (Trade mark without text), 007454523, OHIM, December 10, 2008, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/007454523

- (Trade mark without text), 003592458, OHIM, December 22, 2003, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/003592458

- Case details for trade mark UK00002268693 , UK IPO, April 28, 2001, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://www.ipo.gov.uk/tmcase/Results/1/UK00002268693

- ibid

- ibid at 3, Article 2.1.2.4, ‘Movement marks’, pg. 11

- ibid at 1, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2009:078:0001:0042:en:PDF

- Search for a Trade mark, UK IPO, https://www.gov.uk/search-for-trademark

- ibid at 21

- PANTONE® Colours, last viewed on March 13, 2015, http://www.pantone-colours.com/

- 27/07/2004 R730/2001-4 YELLOW/BLUE/RED

- 24/06/2004 C-49/02 “Colours Blue and Yellow”

- (Trade mark without text) 001526441, OHIM, February 24, 2000, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/001526441

- (Trade mark without text), 011628138, OHIM, March 3, 2013, last viewed on March 13, 2015,https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/011628138

- Michael Schumacher, 001022797, OHIM, December 21, 1998, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/001022797

- >Trade mark UK00001420361, UK IPO, March 30, 1990, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://www.ipo.gov.uk/tmcase/Results/1/UK00001420361

- Gazza, 010543692, OHIM, January 5, 2012, last viewed on March 13, 2015,https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/010543692

- BENTEKE, 013736905, OHIM, February 12, 2015, last viewed on March 13, 2015,https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/trademarks/013736905

- Design Number 002225037-0001, OHIM, April 22, 2013, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/designs/002225037-0001

- Ryder Cup Europe LLP, OHIM, September 25, 2013, last viewed on March 13, 2015, https://oami.europa.eu/eSearch/#details/designs/002225037-0001

- ‘Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks’, European Commission, March 27, 2013, last viewed on March 13, 2015, http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2013:0162:FIN:EN:PDF